MemoryLab

A drag-and-drop web app for teaching Python memory models with guided practice, free-form testing, and automatic grading.

Technology Stack

Key Features

- Scratch-style canvas for building memory diagrams with frames, objects, and values

- Practice mode with structured guidance vs test mode for independent checks

- Question bank of exercises drawn from UofT course material

- Automatic grading with traceable feedback using graph isomorphism

- Exports to JSON, SVG, and PNG for reuse and sharing

About MemoryLab

MemoryLab

Why

During my first years at UofT, one of the most annoying parts of studying computer science was drawing memory model diagrams by hand, it was always such a slog. I wanted an app that made it easy to practice using a drag-and-drop canvas, removing the repetitive work of constantly drawing and redrawing frames and objects. At the same time, I wanted a way to quickly identify mistakes in my memory models, with clear explanations of why they didn’t match the underlying code.

Interesting Technical Points

Drag and Drop Sandbox

The core of MemoryLab is a canvas where students drag and drop memory model objects, just like sketching on paper but digital. The canvas supports all the fundamental Python data types: primitives (integers, strings, booleans), collections (lists, tuples, sets, dictionaries), and custom objects. Each element on the canvas can be connected to others via references, creating a visual representation of how Python stores and links data in memory.

The call stack is also part of the canvas. Students can create function frames that represent different scopes in their program, add variables to each frame, and point those variables to values stored elsewhere on the canvas. This mimics how Python's execution model actually works: frames on the call stack hold variable names, and those names reference objects in the heap.

When a student completes their diagram, the entire canvas state is serialized into JSON. Each memory object becomes a node with a unique ID, type, and value. References between objects are captured as ID mappings, creating a directed graph structure. Function frames are serialized with their variable mappings, and the call stack order is preserved. This JSON representation is then sent to the backend API for validation.

The serialization process builds a graph where:

- Nodes are memory boxes (integers, lists, objects, etc.) and function frames

- Edges are references from variables or container elements to other objects

- IDs uniquely identify each object and enable reference tracking

Validation Algorithm

The validation algorithm treats memory models as graphs and checks for graph isomorphism—ensuring there's a one-to-one mapping between the student's canvas drawing and the expected memory state. The expected model is generated by executing the Python code, and the student's job is to accurately draw what the memory looks like at that point in execution.

The algorithm performs several key checks:

- Frame Matching: Compares call stacks to ensure the correct functions exist in the right order

- Variable Matching: Within each frame, checks that all expected variables are present and no unexpected ones exist

- Type Checking: Verifies that each object has the correct type (int vs list vs dict, etc.)

- Value Comparison: For primitives, directly compares values; for containers, recursively validates structure

- Bijection Enforcement: Ensures each ID in the expected model maps to exactly one ID in the student's canvas (no ID reuse or conflicts)

- Structural Validation: For ordered collections (lists/tuples), checks elements in sequence; for unordered collections (sets), finds a valid matching

- Orphan Detection: Identifies objects that exist on the student's canvas but aren't reachable from any frame variable

The algorithm uses a visited map to handle circular references without infinite loops, and maintains bidirectional mappings (expected→student and student→expected) to enforce the bijection property.

Example Walkthrough

Given the Python code:

a = 1

b = 2

c = a

lst = [a, b]

lst2 = [a, lst, c]

lst[1] = 4

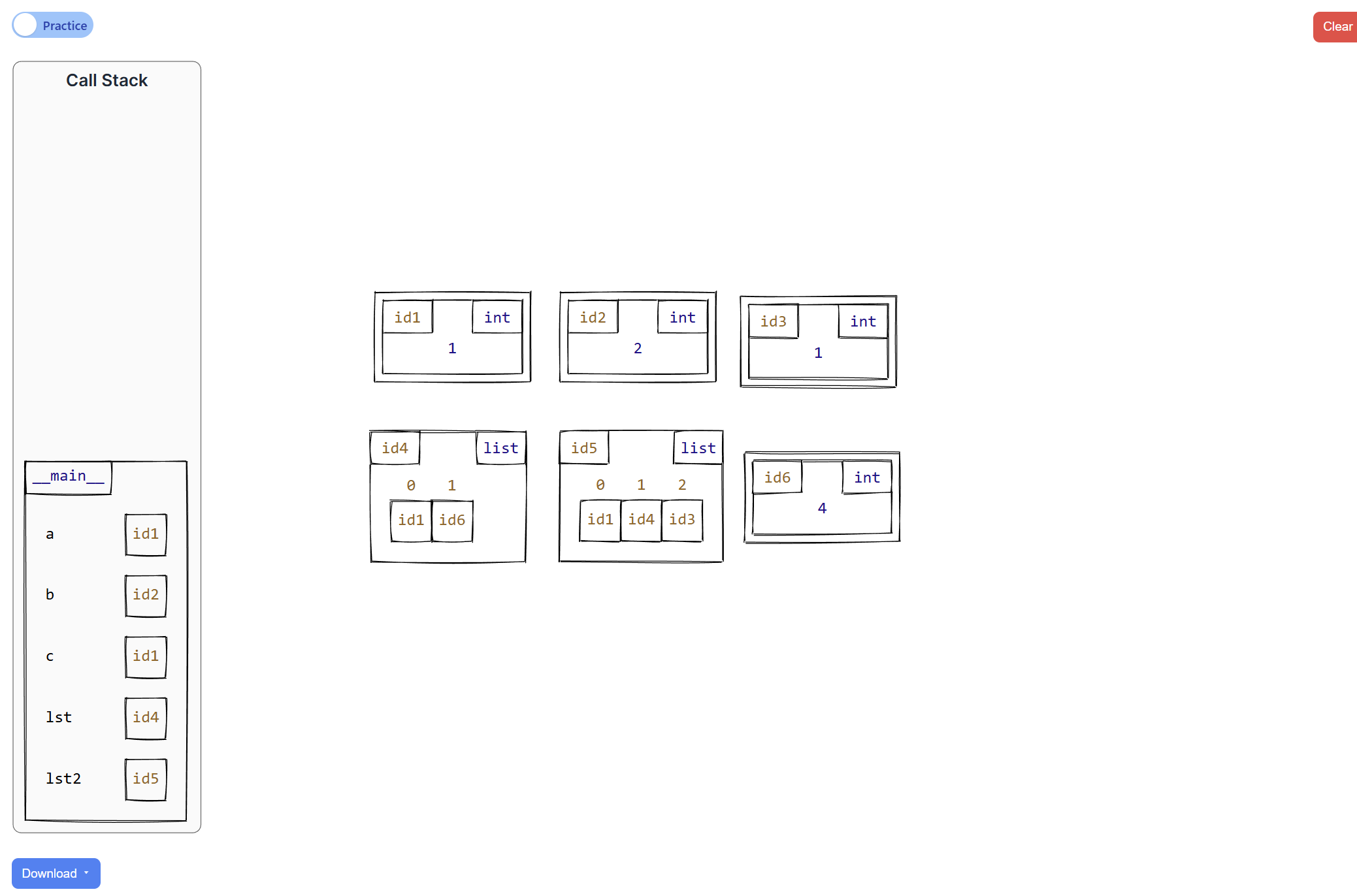

After running this code, the expected memory state is compared against the student's canvas drawing:

How the Validator Checks the Canvas:

-

Frame Check: The expected model has a

__main__frame; the validator confirms the student drew this frame ✓ -

Variable Check: The expected model has variables

a,b,c,lst, andlst2. The validator confirms all are on the student's canvas ✓ -

Variable

a: Expected to reference id1 (int with value 1). Validator checks the student's canvas pointsato the same object ✓ -

Variable

b: Expected to reference id2 (int with value 2). After the mutationlst[1] = 4, variablebstill points to 2, but the canvas must show thatlstat index 1 now contains id6 (int with value 4) ✓ -

Variable

c: Expected to reference id1, the same object asa(aliasing). Validator confirms the student drewcpointing to the same box asa✓ -

Variable

lst: Expected to point to id4 (a list). The validator recursively checks each element:- Index 0 must reference id1 (value 1) ✓

- Index 1 must reference id6 (value 4, after mutation) ✓

-

Variable

lst2: Expected to point to id5 (another list). Validator recursively checks each element:- Index 0 must reference id1 (same as

aandc) ✓ - Index 1 must reference id4 (the

lstobject) ✓ - Index 2 must reference id1 (same as

a) ✓

- Index 0 must reference id1 (same as

-

Bijection Check: Ensures the student's ID mappings create a perfect one-to-one correspondence with the expected model (no duplicate IDs or misaligned references) ✓

-

Orphan Check: Verifies the student didn't draw extra objects on the canvas that aren't referenced from any variable ✓

The algorithm returns a detailed error report if any check fails, highlighting exactly which object or reference is incorrect on the student's canvas.

Error Visualization and Feedback System

The validation system doesn't just return a pass/fail result—it provides structured, actionable feedback that helps students understand exactly what's wrong with their canvas. Each error includes:

Error Structure:

- Error Type: Categorized as TYPE_MISMATCH, VALUE_MISMATCH, MISSING_ELEMENT, UNEXPECTED_ELEMENT, DUPLICATE_ID, ORPHANED_ELEMENT, etc.

- Element IDs: Numerical identifiers of the problematic objects on the canvas

- Path Information: The chain of references leading to the error (e.g.,

function "__main__" → var "lst" → [1] →) - Detailed Messages: Human-readable explanations comparing expected vs. actual state

- Severity Levels: Errors, warnings, or info messages to prioritize what needs fixing

Visual Highlighting:

The real power of this system is the visual feedback. When an error is detected, the element IDs are used to highlight the incorrect objects directly on the canvas. For example, if a student incorrectly maps variable a to id3 instead of id1, the system highlights both the variable in the frame and the incorrectly referenced object, making the mistake immediately visible.

For errors involving multiple elements (like missing list elements or aliasing issues), the relatedIds field ensures all relevant objects are highlighted together, showing the full context of the problem.

Example Error Messages:

- Type Mismatch: "Type mismatch: function 'main' → var 'lst' got int, expected list" (Highlights the variable and the incorrectly typed object)

- Value Mismatch: "Value mismatch: function 'main' → var 'a' got 2, expected 1" (Points to the specific primitive value that's wrong)

- Missing Element: "Missing element: list[1] id=4" (Highlights the container and indicates which element is missing)

- Orphaned Element: "Unmapped box: id=8" (Highlights objects on the canvas that aren't referenced from any variable)

- Duplicate ID: "Duplicate ID: 5" (Highlights all objects sharing the same ID, a common student mistake)

All errors are consolidated in a dedicated Errors Tab, providing an easy-to-scan list of all problems. This tab acts as a checklist: students can work through each error one by one, fixing issues on the canvas and seeing the highlighted elements update in real-time. The combination of the error list and visual highlighting on the canvas makes debugging intuitive and systematic.

Iterative Learning:

This feedback system transforms debugging into a learning opportunity. Instead of trial-and-error guessing, students can:

- See exactly which objects are problematic on the canvas (visual highlighting)

- Understand the reference path that led to the error (path information)

- Compare what they drew vs. what was expected (detailed messages)

- Fix the specific issue and resubmit immediately

The system handles complex scenarios gracefully: circular references, nested containers, aliasing bugs, and call stack errors all produce clear, localized feedback. Students learn to think about memory models more precisely because the feedback directly reinforces correct mental models.

What I Learned

How to build core interactive experiences in web apps, mainly pages, portals, and tools, building on my previous experience and pushing into more complex UI state and interactions.

Designing and implementing custom algorithms to validate user work. In particular, building a validation system that compares two memory models, checks structural equivalence, and handles tricky cases like shared references and cycles, while keeping results consistent, covering edge cases, and avoiding noisy false positives.

Improved web design and development skills, including layout, spacing, and overall UI clarity, while also working closely with backend systems to keep the experience fast, reliable, and easy to iterate on.

How to write clearer, more actionable feedback so students can understand mistakes and fix them faster, and how to integrate that feedback into a clean, compact UI that stays out of the way and helps them work through issues one problem at a time.